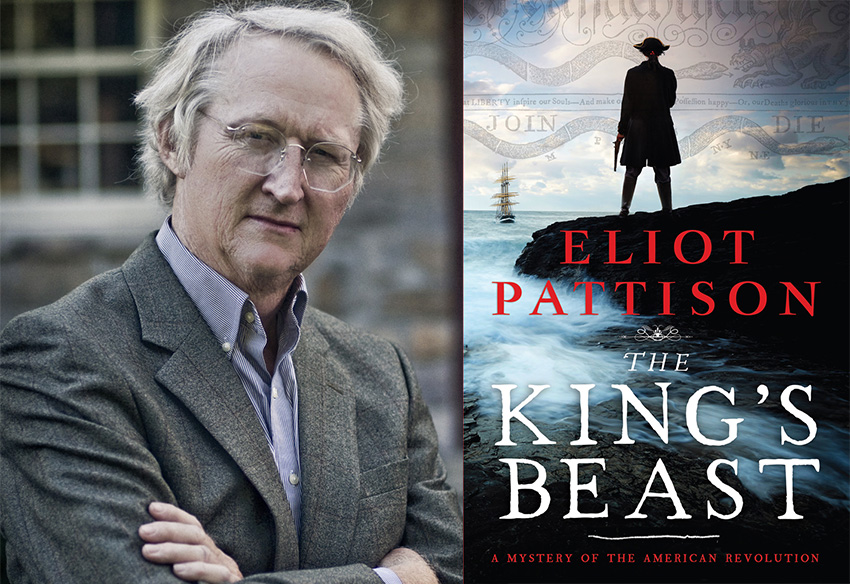

Eliot Pattison – The King’s Beast

Elliot Pattison to talks about his latest novel The King’s Beast: A Mystery of the American Revolution.

About Eliot Pattison

An international lawyer by training, early in his career Pattison began writing on legal and business topics, producing several books and dozens of articles published on three continents. In the late 1990’s he decided to combine his deep concerns for the people of Tibet with his interest in venturing into fiction by writing The Skull Mantra. Winning the Edgar Award for Best First Mystery–and listed as a finalist for best novel for the year in Dublin’s prestigious IMPAC awards–The Skull Mantra launched the Inspector Shan series, which now includes eight novels – both The Skull Mantra and Water Touching Stone were selected by Amazon.com for its annual list of ten best new mysteries. Water Touching Stone was also selected by Booksense as the number one mystery of all time for readers’ groups.

The Inspector Shan series has been translated into over twenty languages around the world. The books have been characterized as creating a new “campaign thriller” genre for the way they weave significant social and political themes into their plots. Indeed, as soon as the novels were released they became popular black market items in China for the way they highlight issues long hidden by Beijing.

In 2015, Eliot Pattison received the prestigious “Art of Freedom” award from the Tibet House along with the likes of radio personality Ira Glass, singer Patti Smith and actor Richard Gere for his human rights advocacy in Tibet.

Pattison’s longtime interest in another “faraway” place, the 18th-century American wilderness and its woodland Indians–led to the launch of his Bone Rattler series, which quickly won critical acclaim for its poignant presentation of Scottish outcasts and Indians during the upheaval of the French and Indian War. In Pattison’s words, “this was an extraordinary time that bred the extraordinary people who gave birth to America,” and the lessons offered by the human drama in that long-ago wilderness remain fresh and compelling today.

Praise for The King’s Beast

“Set in 1769, Edgar-winner Pattison’s sixth mystery featuring Scottish exile Duncan McCallum (after 2018’s Savage Liberty) surpasses the high bar set by the previous five adventures . . . Pattison keeps the suspense high throughout. This triumphant combination of whodunit and deeply researched history should help this gifted author get the wider audience he richly deserves.”— Publishers Weekly

About The King’s Beast

When Duncan McCallum is asked by Benjamin Franklin to retrieve an astonishing cache of fossils from the Kentucky wilderness, his excitement as a naturalist blinds him to his treacherous path. But as murderers stalk him Duncan discovers that the fossils of this American incognitum are not nearly as mysterious as the political intrigue driving his mission. The Sons of Liberty insist, without explaining why that the only way to keep the king from pursuing a bloody war with America is for Duncan to secretly deliver the fossils to Franklin in London.

His journey becomes a nightmare of deceit and violence as he seeks the cryptic link between the bones and the king. Every layer that Duncan peels away invites new treachery by those obsessed with crushing American dissent. With each attempt on his life, Duncan questions the meaning of the liberty he and the Sons seek. His last desperate hope for survival, and the rescue of his aged native friend Conawago–imprisoned in Bedlam–requires the help of freed slaves, an aristocratic maiden, a band of street urchins, and the gods of his tribal allies.

Good evening. This is Neil Labute and you’re listening to center stage with Mark Gordon. Santa Stage, Santa stage, Santa Santa Santa stage.

Santa stayed. Yeah. Welcome to center stage. My name is Mark Gordon. On this program, we’re going to talk with Elliot Pattison. He’s the author of the King’s Beast, a mystery of the American Revolution. Interesting thing about him. He started his career as an international lawyer and he traveled all over the world, and a trip to Tibet changed his life and his career for ever. You’ve travelled pretty much every continent. Except for Antarctica. Is Antarctica next on the list? If when the craziness dies down, yeah, it’s on the bucket list. One of your travels took you to Tibet. What was it about Tibet? Tell me about that first time that you visited the country and what impact did it have on you? So I went in after having studied Asian religion, especially Tibetan Buddhism, which had always interested me fairly significantly and and and and also having been a student of Asian history and a student of Chinese tradition. So I I went in with that background. And at first was blown away, amazed, you know, in a positive way because of the, the physical, you know, reflection of the culture is still the physical reflection of the culture, which at that time still mostly there. And so the old, there were still quite a few old temples and you could see signs of the Tibetan civilization and I and I call it civilization very meaningfully because I do believe they added you know, what was essentially a separate. Civilization from the Chinese. But then the more I experienced it, you know, my amazement turned to confusion,

which then turned to outrage. Confusion because I realized that there were many, many examples, but most poignant would be in temples. The Tibetan Buddhist monks were very, very closely shadowed by Chinese policemen everywhere they went. It was like one-on-one policeman with a Billy club. Standing behind a Tibetan monk who was simply sitting, meditating. And then there would be spots where I would walk in and they would see me, a foreigner, and they would tap all the monks on their shoulders with their Billy clubs and push them out of the door because I had come in. At first I was sort of like. Confused. But as I, as I studied, you know, as I experienced more but also studied more, read an awful lot more of of Tibetan chronicles first hand. Chronicles of Tibetan, what you would, I would now call survivors. It’s rational Tibetans who who were present during the initial Chinese occupation. I began to to realize that this was quite remarkable. Civilization was being systematically destroyed by a real sort of jackbooted tyranny out of Beijing. And I had written a lot of. Um, different kinds of nonfiction legal treatises and a couple of business policy, business and policy books. I really wanted to try my hand at fiction. At the same time, I wanted to tell the world about Tibet and what was going on. And I had this epiphany that I could write it, write a mystery set in Tibet that would, as a deep background, have the the Tibetan culture present on the stage in the in the course of of mystery being solved by a Chinese investigator, and that turned into the school. Mantra and, you know, school. Mantra won the Edgar Award that year. I had no idea how it was gonna go. It’s very familiar story for starting, you know, struggling novelists tried to place it myself and got rejections

from every publisher first to majors in the minors, but all of them rejecting, and with several comments for those who took the time to actually read some of the manuscript, I would get notes back saying nobody would be interested in in Tibet. Sorry, some would say, like nobody’s even heard of Tibet. Why would you write a mystery set? Then I turned to an agent who and I was very lucky. She loved it. And then she said immediately. I know exactly the right editor to send this to. Because, you know, an awful lot of publishing revolves around the the views of an editor and the sponsorship of an editor. And so it was a few short weeks I had a contract with with Saint Martins and then in short order won the Edgar and then a contract for more of the of the books. Before too long the books were being published in 20 languages around the world. What do you think is your biggest challenge? I mean obviously there are different stages where first you. Want to get published and that’s the whole challenge in itself. But now the place that you’re at, do you still encounter challenges and have they changed and how do you overcome those? Most fundamentally, say it that way the most the biggest challenge is just the discipline. When I make appearances face to face with people, I almost always get the question of how first, how often do you have novels? And I’ll say one a year, and they’re, and they’re like, how could you possibly do that? My books are pretty complex. Reviews often talk about them being very densely plotted, which you take both ways. But I, you know, I sort of take pride in that. And I’ll say, listen, it’s discipline. And no matter where I am, no matter what I’m doing, I spend 2 to 3 hours a day writing. And when I spend 2 to 3 hours a day writing. That gets me a novel a year. You can’t just say, Oh yeah, I’ll write a couple hours a day and have a guaranteed success. I mean, there’s a lot of other challenges about being a writer, and I’m reminded often of of Mark Twain. What we owe asked about the process

of writing and he said it’s all about finding the right word. And the difference between the almost right word and the right word is the difference between a lightning bug and lightning. And so I probably appreciate that even more after years of writing. Addiction. When I go through a final edit of a piece, it’s getting to that very precise word that works in terms of the character being authentic to the character who’s speaking and and you know in the scene that’s being described. And the English language is extremely rich and and it’s a great pleasure when you know you did find that right word. You said once that the world we have created works against the preservation of culture, religion and fundamental human values, and I think about that based on what you told me and what I’ve read about you in Tibet. When I was a lawyer in my professional career, I worked. All over the world and advised governments and big corporations and actually advised the Chinese government. I had a lot of experience with the Chinese Government as well as a lot of other governments in Europe and South America. And so I think I have a sort of better than average understanding of the global economy and and global legal structures and and the way governments work around the world and and relate to each other you know across oceans as it were. You know to put it in a nutshell. As somebody who also tracks your observes and writes about human rights, we’ve allowed material things and financial goals to to preempt everything else, including human rights and fundamental freedom. And I think there’s no better example of this than what happened this winter with the with basketball and China, where the people in Hong Kong were protesting, asserting their fundamental freedom against some some measures of tyranny. Even waving American flags and I, you know,

and I’m not trying to be jingoistic, you know, about American flags, but I mean always as a symbol of freedom. They were, they were waving these flags. And the general manager of the Houston basketball team, I think it gave a tweet supporting the people of Hong Kong. And the Chinese government went berserk and the NBA was all over him and other players in the NBA all over him criticizing him because they they didn’t want China to pull back on all the base. All the basketball coverage they were providing and the and the big the NBA actually has a schedule of games. And then in in China and this is and to abbreviate conversations I’ve had through in recent years in a lot of places it’s like. Isn’t it, you know, I’ll describe the terrible things going on in Tibet or sometimes in Xinjiang with the Uighurs who are, you know, being thrown into a gulag prison system and, you know, just north of Tibet by the Chinese government and people who say, oh, that’s really awful, we need to do something about China. But, you know, the answer is yeah, but I really like my cheap tennis shoes. I really like my jeans, designer jeans that are made in China. That’s distilling a lot of a lot of perceptions, but that’s what it comes down to. I think we need to recalibrate what’s going on right now with the pandemic may be pushing recalibration both in the US and and in Europe around these sort of issues. Is this a recurring theme within your work? It’s absolutely a theme. And I’m actually just finishing up an essay post for crime reads, which is on the role of dying cultures in in crime novels. Every novel, and I’ve done 17, as I mentioned, everyone of them features a dying culture. Features, and that implicitly means features, human rights that have been trod on by a stronger power, whether it’s China versus the Tibetans or China versus traditional Chinese. Because my main character of the Sean Books

is a very traditional Confucian type, Chinese detective. And he’s been crushed as well. His family was destroyed. By the regime in Beijing. So it’s not just the Tibetans. And then in my 18th century books, we have the slaves, African slaves that also there were. People don’t focus much on this, these, you know, in in our, in our history books. But there were Native American slaves, a lot of them, especially in the in the late 1600s and early And there were a lot of Scottish slaves who were sent over as indentured servants, servants, but wound up basically being treated like slaves very often, especially if they went to the South. I could spiculus in the in this series are the Native Americans and what’s happening to them in the mid 18th century, and the Highland Scots and the Scots and the Native Americans are experiencing a very similar disruption, a lot of parallels and destruction of their culture. My books used that as a backdrop and I believe that the genre of historical fiction and especially historical crime novels provide a really, really great palette. They’re painting those pictures and, you know, and developing those themes. Why did you become, should I say, obsessed with the 18th century? I would just say I have a a normal curiosity and everybody else is sort of lost their curiosity but I but because I think the 18th century is very very important for for all of us. When I was young my parents would take us to many many historic sites including a lot of Revolutionary War sites. We would go to Valley Forge just about every summer and walk around. And so at an early age I was very impressed with that history and back in the day when I was young you could go to Independence Hall and. Hug the Liberty Bell, which I did many times. Today you would be arrested. Wait, hold on. That’s not why it cracked as it.

Yeah, I’m sorry. I was. I squeezed it tight one time. So I connected an awful lot with the 18th century history where I lived as a boy. We had a lot of Native American artifacts available. Local farmers would show me and my friends where old campsites were. And you could sort of just like run a stick in the ground, make a furrow in the sandy soil, and you would almost always find some Indian artifacts, some Native American artifact. And that was fascinating to me as well. And so. At an early stage I had this real sense of wonder about the 18th century, but then as I studied, as I became more of a. Student of history, I realized that the mid 18th century, 17501755 onward was really, truly a remarkable time in the history of of of mankind. There was this explosion of self-awareness, the expansion of printing and literacy. There was an explosion of printing presses and suddenly people who never received newspapers, you know, people in small villages and Allen Farms, suddenly they had newspapers available. Political tracts and religious tracts and the works of Shakespeare, etcetera, etcetera. And in fact it’s been demonstrated in many ways. The population of America, the American colonies was much more literary and much better red than the people of of England. You know it’s kind of interesting when you think about that. They read more books than than people in Britain did. There was a huge explosion of of what we would call science back then. They they just called it natural philosophy. That’s actually a very important theme and and really even a plot line in Mike in the King’s beast. In my new book, it’s it’s very much about the interface between science and the establishment. And I say it that way because science became a very important, empowering dynamic for a lot of Americans and a lot of people that supported liberty in England. If you want to know more about that, read the King’s beast because it it’s, it reflects it, I think,

very well. There was a Broadview in what for shorthand purposes, I’ll call the establishment. That scientific knowledge was something that was preserved for the king and the royalty and the, you know, the nobility of the of the, the upper upper class. And that was true all over Europe, true in a lot of other cultures as well. And this book I wanted to very much focus on the juxtaposition of scientific development and political development. And so I knew there were a lot of interesting things that were happening on. Call it the scientific stage. At that time I was really astounded by how much this is and I should mention these books are called mysteries of the American Revolution, because I really believe that. I actually discovered that a number of prominent founding fathers said the same thing, but only after I’ve been saying this in in public appearances for a while, that the real revolution happened before the first shot was fired at Lexington and Concord. The minds and the hearts of the people were turned during the 1760s, in the early 70s. 70, Seventeen, Seventeen, and that’s very much of the theme. So back on Science James Watt had in that year he obtained his first patent for a steam engine. If you ask people when we’re steam engines developed, almost everybody would say probably or I kind of remember that ships of the Civil war had steam engines, for example, but no, it’s They had introduced steam and they were developing applications for steam engines. Be used in mines in England. And people were already talking about trying to make machines that could be moved by steam power. OK you know look eventually locomotives. The Mason Dixon line had just been completed. And this actually figures into my plot. I have a lot of scientific perspectives that come together in a very interesting, interesting way in this book. It was a lot of fun to write. There is the Mason Dixon line, which you just completed, and Charles Mason who, who and and that I didn’t realize this. Mason Dixon. I always

thought it was some surveyors. The transit and you know like you shoot a straight line and you mark and then you shoot the next line you market. No, it was a four year project and they took celestial fixes every night. They did celestial navigation to be sure. It was absolutely precise. And so there was a huge amount of mathematical calculation that went into the Mason Dixon line. And in the course of this they taught a number of Americans about astronomy. And so then. 1769 transit of Venus occurred, which is the passage of the planet Venus visibly across the face of the Sun. Nobody knew how far the sun was, and it was like one of the great quests of scholars in the in the seven in the 16th and 17th and 18th centuries to figure out how far away the sun was. And if you do, you know the algae well. It’s trigonometry comes into a geometry and trigonometry, right? You can you time it the Venus when it crosses the first edge of the sun, and then you take a fix when it crosses the. When it leaves the edge of the sun and you can actually create a triangle and do the trigonometry calculations to come up with the distance. I mean, it’s very complicated, but it’s, you know, it’s scientific improvement and. In 1769 the king had declared that he was going to find the distance to the sun, and it was. It was again back on this point about the aristocracy controlling science. The king, for example, had built the built it still exists, and observatory or roll observatory in what was Kew Gardens just to observe the transit because he was going to be the one to make the calculation and he didn’t get to do it. The weather wasn’t great and he didn’t, you know, they didn’t have all the right calculations. And, you know, so it was very important at the time. It was in the newspapers all the time, people talking about preparation for the transit of Venus. And Gee, a bunch of these rebellious Americans, some of whom have been taught by Charles Mason about astronomy, said we can do this. And Charles Mason, the poor

guy, went back to London, and in talking about his accomplishment, he explained how he also was able to teach a lot of Americans about astronomy, and the upper class went berserk over that. They thought that was terrible. And so they said, never got the accolades that he should have for the amazing work that he did. But the people that he trained in mostly Philadelphia and there were some very prominent names like Rittenhouse and Biddle who were involved in this. They were the ones who ultimately got the first calculation of the distance to the sun and the king was furious. And so that’s also part of this book. It’s very interesting. It’s true. It’s all fact based. You can look it up. They had to finally admit that some amateurs. In Philadelphia and his world astronomer actually publicly gave a speech about this that you know as amateurs in Philadelphia incredibly were able to to calculate the distance to the sun. It was like a concession made and people were quite angry and the London were quite angry that the absurd Americans would do this. On the on the other side of the Atlantic the Americans got very very excited and it sort of was another facet and there were many facets to the new American autonomy. We can do this. We can do, we’re just as good. In scholastic or scientific pursuits. As the guys back in the court in London. And that sort of development, that sort of mentality of progression of of perspectives, that was more than anything the revolution that caused our independence. That’s really fascinating. We think about that, you know, got a bunch of guys sitting around in Philadelphia came up with the idea that they would calculate the distance to the sun and then they actually did it. It was a major recalibration in terms of the the, the, you know, the academic community, the scientific community at the time you mentioned that Americans have become disconnected from. Human drama in our country’s founding and also that the textbooks seem to dehumanize history. How important is that to us as a culture? I think

it’s extremely important and, and you know there are many facets to this issue. First of all the the, you know, our formal educators, the educational institutions have dramatically deemphasized history. You could argue it started decades ago when the federal government started to take over the formation of curriculum and local schools and that was back in the Bush administration. History was quickly dropped from the core curriculum and so in many schools. In high schools, history is is an elective. It’s not required. And the number of history courses available in colleges have gone dramatically down. There’s different tests showing that 8th graders know more about American history than high school graduates, and high school graduates know more about American history than college graduates. David McCullough, who’s you know well well known for writing historical nonfiction, wonderful historical nonfiction, has talked about how you can’t be a meaningful participant in our democracy if you have no history. We are the past. I mean, we are absolutely the result of the past. And if you want to know about our government, you can’t understand it if you don’t study the past, and especially those who who just only know about history from old textbooks, which are very dry and boring and, you know, not humanizing, you know, very dehumanizing, humanizing of history. I try to breathe life into characters and I always include well known figures from history, but I try to breathe real human breath into them. So in this book, the King’s Beast, Ben Franklin winds up having a very. Important role. And there are a lot of really interesting aspects of Franklin that aren’t in the history books. Ben Franklin was a really fascinating, was kind of a rogue, but he was, he was very compassionate. He had a deep curiosity about everything. He had really odd personal habits. He had a habit that he pursued his entire life. Every morning he got up and he would sit naked in a chair and read the newspaper

for an hour. He called that his air bass. He would invite people to join him. Usually people were would not, but every day, and there’s records of this in London and I have this in my book, my protagonist and shocked and Franklin invites him into his bedroom and he’s sitting there naked reading the paper. And Franklin invites you the tickets clothes off and join them and it’s like. And so I love that it mean that that happened to people. We know that Franklin took his air bath every day for decades, and we know that he invited people to join him. And so it’s not a stretch that strangers would come in and find Ben Franklin naked in the chair. And. He pursued a lot of adventures throughout his life. And. He did all kinds of interesting things with electricity he had. A lot of electrical apparatus in his home in London and he would sort of like shock people for entertainment. And, you know, there were just these many, many interesting, you know, human facets of of these characters that you don’t see in the history books. You don’t find history textbooks or disappearing, but even the ones that are there don’t humanize our, you know, historical figures this way. This book with Franklin, he is he’s living in London and I have. His address and his landlady and and and a lot of description of his household, which is available with you. You know, if you do the research and I love that stuff and you know, it makes people come alive and then you begin to realize, my gosh, I mean Ben Franklin could walk through the door today and I would recognize him from the description. These really were real people. They didn’t just sort of exist in a cartoon or exist in some bubble in a comic book describing an event or a timeline and some history text didn’t live in the past. That was the present to them. And they were dealing with real important issues, especially, you know, during this. What is your creative process like now? I was reading that. You don’t do outlines. Yeah, it’s always frustrating in my publishers. So they’ll say, you know, give

us, you know, give us an outline of your next novel. And I’ll say, well, here’s the, here’s the broad, here’s the broad themes I’m going to be exploring in the novel, you know, but it’s not an outline. It’s not a, you know, they, you know, they’re expecting like a some sort of a plot formula. So I have very strong protagonists. I know my protagonist really, really well, actually. And I think this is a really good exercise for anybody that writes a series like this. I have like a biography file of my protagonist and I flesh out their lives and and include details that never appear in my books. So I know them. And it’s not just one protagonist. In each book there’s one primary character but then there are others that recur like in in the bone Rattler series and the you know the of which the King’s beast is the latest one. The closest friends from my protagonist whose name is Doctor McCallum. Our Native Americans. And so they’re featured you know repeatedly through the series so I know that. I know the characters. I know like in this book in the very early stages, I knew I was gonna have a focus on these fossils, which really fascinated me. There’s a lot, a lot of good, you know, it’s really interesting history around the fossils of this place called the Big Bone Lick in Kentucky, where it was first discovered by Europeans. And the Indians are known about it for centuries before. But when the Europeans described it, it was this big mud flat that was had a lot of sulfur fumes, you know, coming out of the ground. And the bones of hundreds of animals, and now we know that many of them were mastodons, but there were also a number of other Ice Age animals that died there. And so that fascinated me. And I knew that there was a lot of interest in Europe about the about the bones and people were asking for the bones to be brought over to be shown to royalty and there were a lot of people writing things about them. There have been some similar bones found in the Hudson Valley and in the in the. By our century and everybody had decided they were bones of

giant men. My guy, Duncan McCallum, that his friends, they have no idea what the bones are. They just know they’re mysterious. Duncan’s, you know, medical, medical training, he’s fascinated by them and he knows Ben Franklin wants them. And in fact, it’s a secret mission for the Sons of Liberty to get the bones to Ben Franklin. He’s not told why, and he learns through a lot of intrigue and violence that they’re all part of a of a political intrigue in London. They’re very politically explosive. So with 17 novels. You obviously don’t deal with writers, Brock. Or do you? Well, it’s all relative, I would say. Does it exist? Does writers block really exist? Well, I would say so. I mean, I I think, yeah, there are days when I I was sitting staring at me, yelling. Especially when I’m editing. Trying to figure out where to take a scene, make it sharper and make it more interesting. Sometimes I just don’t get anywhere. I’ll I’ll get through 2 pages when I was aiming to get through 20 pages on an edit. So I I think it exists. We know that it’s connected because oftentimes writers or directors or artists, they keep going back and back and revising. When do you know that I need to cut bait? This is good. I think for most novelists.

The novel was finished because it’s due under a contract, so you always have that clock ticking. I’m not trying to mock the process. I know what it takes to get the novel done, and I will have a lot of, you know, much more intense writing in the in the two months before a manuscript is due, no question. But there is a very, I think it’s very subjective judgment as to when something is ripe enough to to pick. You know as the right as the author, you know this character, you know how you want this character to feel, what type of emotional and the how intense the emotions will be in this scene and they should be. And that you’re trying to convey this point out of the mouth of this person and and you know, it comes back to authenticity. But not, you know, it’s not just authenticity factually, it’s being authentic to the characters. And also adding to to. You know, the broader goal of the book, who sets the goal for you for a year a book? Is that your publisher or you just do that, that’s you’re driven to do that. So the publishers prefer that right when, especially when you write a series. And so I, I I agree to it in contracts, right?

It’s a mutual thing. I mean, I know what I’m getting into. But I, you know, I always have contracts out, you know, for my my books and and.

I’ve driven to meet the deadlines. But sometimes I’ll be doing the final edit of a book when I have to be writing another book, and that can get pretty confusing. But that’s happened. What motivates you? I want to get these messages out there. I have a lot of deep, you know, you know, deep satisfaction of of sort of the job well done when I get your book finally in print. I think it really is important to get these these messages about history out there and to get people excited about history and in new ways. That’s a big motivation from a broader literary sense. I very much worry that people are moving away from the written word and in my experience. There is a lot of intellectual curiosity that’s kind of being wasted these days. It could be much more constructively used by picking up a good book. You know and there’s and there’s a there’s encouraging signs you know along these lines of the other quality of mysteries and this is something that I, you know, that that affects me and I mean I find there are reviewers and and and and even bookstore owners that sort of traditionally have put. Uh, mysteries off. You know, sort of an aside niche. Uh and, and I’ve had people tell me. I said an appearance in Boston a couple years ago where a woman came up and said, God, you’re such a good writer, why don’t you write a real novel?

I mean, why do you just write mysteries, you know, and so, you know, there’s there’s other phenomena that I that I really enjoy being part of of making mysteries more literary, you know, and I, and I’m often, you know, called a, you know, writer of literary mysteries. I mean, people have a hard time characterizing my books, but one of the labels they give is, is literary mysteries, which is fine with me. So look, I am driven by those things. I mean they sound, you know, sort of. You know, ambitious and vague, but but they’re important to me. Well, do you have anything else to add, Elliot? No, I think that I just, I really appreciate the conversation, Mark. I think these encourage people to go out and take a look at my books, the new ones, the King’s beast. But also to to, you know, just go look at historical fiction. There’s a lot of good stuff out there. Well, thank you so much, Elliot, and we’ve been talking with Elliott Patterson. The name of this book is the King’s Beast, a mystery of the American Revolution, and that’s going to be available on April 7th. You write freehand, right? You actually get a piece of paper and a pen or a pencil and absolutely, yeah, the first drafts you. Yeah, I find. I mean, that’s what I do, you know, of course I’m gonna, you know, from an older generation and, and that seems natural to me. I’m constantly editing. So that would then when it goes into the word processor, I’m changing it as I enter it. But yes, I do very much have the manual process. I mean I was flying across the Atlantic a couple of years ago and. After we landed at Heathrow, good guy near me, they grow behind me, he says. You know. Everybody in here, unless if they weren’t

asleep, they were working on their laptops or iPads and you’re the only guy in this whole section of the aircraft that was actually writing something.

It’s like, yeah, I said, you know, I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but that’s, yeah, that’s who I am, right? Well, does it engage a different part of the brain because it’s a different process altogether, writing with your hand and a pin or typing? Does Mark, if you look at the really interesting studies out about. In the elementary schools now, a lot of a lot of schools are not teaching handwriting to their students, and they’re finding a lot of interesting connections, mostly negative connections in terms of the way the brain works when when children are not learning to write. Or to put it another way, the children that learn to write have a lot more synapses firing when in their in their learning process than the other ones. There’s a certain physical satisfaction you know, to be had. All right, Elliot. Thank you so much. Thanks, mark. Bye, bye. Here. Just a reminder, Elliott Pattison’s the King’s beast, a mystery of the American Revolution is available on Amazon.com. Until next time, this is Mark Gordon and I’ll see you center stage.

Sign up with your email and always get notifed of Avada Lifestyles latest news!