Tim DeRoche Inequality in America’s Public Schools

Several years ago, I met Tim DeRoche when he published The Ballad of Huck & Miguel. This time around, we met via Skype to discuss his new book, A Fine Line: How Most American Kids Are Kept Out of the Best Public Schools, which sheds light on the inequality in America’s public school system.

Mark Gordon: How would you best describe this book?

Tim DeRoche: This book is about the laws and the policies that assign kids to public schools based on their residential address. It’s something that most people just accept as a given. It’s been a part of the American fabric for so long, we just take it as a given, and my book is about the problems that it causes. It’s a social justice angle in the sense that many middle-class and lower-income folks are excluded from the best public schools in a given city or a given district. But there are all sorts of distortions that those policies inflict on American life. So my book is about those policies and how they affect us, and it’s about, can we reconcile those policies with some of the principles of our democracy, like equal protection. Like the idea that public schools are the great equalizer. Like the idea that public schools should be open to all, which many in the state’s constitution promise.

Mark Gordon: You have been involved in education for about 20 years.

Tim DeRoche: Yeah, it’s something I felt strongly about for a long time. I have always found myself drawn to kids. I have a very empathetic feeling for children for a variety of personal reasons, and in high school, we had a service program where we had to go out into the community for two weeks. We would stop studies and go out into the community, and I volunteered in a public elementary school in urban Millwalkie, and it was a disturbing place to be. I volunteered in a number of different classrooms and could see that the second graders, for example, weren’t all that different than second-graders in the middle-class suburb where I grew up. They were different races. They were probably lower income. They were urban rather and suburban, so they had some differences. But you could tell that they were still kids and still had the full potential of any other second-grader any other seven or eight-year-old. But then when [I’d] go to the sixth-grade classrooms, it was quite a different experience, and the kids were troubled. They were way behind academically. There was one kid; in particular, he wasn’t clean every day. He was disruptive in class. The teachers in those sixth-grade classrooms were very disillusioned and not as engaged as you would want a teacher to be in a classroom with lower income sixth-graders, right on the brink of middle school, on the brink of high school. You would want those middle school teachers to be believing in those kids and sending them that kind of message, and that’s not what I saw. And so it was something I felt passionately about. As you know, I have done some creative things over the last, in my adult life, I’ve done some work in the business world but never really have stopped being engaged with public education and public education reform and so I have worked with a lot of different non-profits, sometimes as a volunteer. I volunteered at some inner-city schools here in Los Angeles but also helping non-profits who are active in education reform with their strategy about how they are trying to make an impact on schools and kid’s lives.

Mark Gordon: How did you get involved with Gloria Romero, former Majority leader of the California Senate?

Tim DeRoche: Gloria wrote the afterword of my book. She’s become a very good friend. I was hired back in 2013, she had just left the senate, and she was the head of the L.A. Chapter of Democrats for education reform. She was trying to figure out how her life was going to look post legislature, and she was out in the mitts of giving a bunch of speeches about how your zip code should not determine your educational destiny. So we meet for coffee in El Serrano at the Starbucks there. I still remember it very well. She was telling me about her speeches, and we were brainstorming. There were a couple of lawsuits going through the courts at that time about the schools, and so I sort of had the legal angle on my brain, and I asked her. I lived in Silverlake for many years.

Ivanhoe is a very sought after school in Silverlake, and it matters whether you live on one side of the line or the other in terms of whether you get to go to Ivanhoe or not. And it matters how much your house is worth. So the equivalent [home] on one side of the line or the other might be worth $200,000 more. So, if you are a middle-income family, you’re struggling to afford a house in that Ivanhoe zone because most of the folks who go there are more affluent. So, in the context of that, I asked Gloria. Well, I don’t get it. What’s the legal basis for [the district] keeping kids out of that school if they live within walking distance of Ivanhoe and live within the borders of the L.A. Unified school district? [People] who live in Silverlake [are} paying for Ivanhoe, both via their income taxes that go to the state and end up funding that school but also via property taxes and school bonds which go to Ivanhoe. So I just started wondering, it just seems like somebody who lives in Silverlake, who lives within walking distance of Ivanhoe, should have an equal opportunity to enroll. What is the legal basis for that school saying no, sorry you can’t, you’re not allowed. We only take people within these lines. That central curiosity leads me to start researching this issue and to surprize after surprize. It started just like a passion project, and the surprises kept coming. At a certain point, I was like, this is an untold story. I think there is a lot of stuff here that nobody [is] aware of. Even though I’d been working in education reform for a long time, I didn’t know about this stuff. And so I wanted to tell that story. So this book is that story.

Ivanhoe is a very sought after school in Silverlake, and it matters whether you live on one side of the line or the other in terms of whether you get to go to Ivanhoe or not. And it matters how much your house is worth. So the equivalent [home] on one side of the line or the other might be worth $200,000 more. So, if you are a middle-income family, you’re struggling to afford a house in that Ivanhoe zone because most of the folks who go there are more affluent. So, in the context of that, I asked Gloria. Well, I don’t get it. What’s the legal basis for [the district] keeping kids out of that school if they live within walking distance of Ivanhoe and live within the borders of the L.A. Unified school district? [People] who live in Silverlake [are} paying for Ivanhoe, both via their income taxes that go to the state and end up funding that school but also via property taxes and school bonds which go to Ivanhoe. So I just started wondering, it just seems like somebody who lives in Silverlake, who lives within walking distance of Ivanhoe, should have an equal opportunity to enroll. What is the legal basis for that school saying no, sorry you can’t, you’re not allowed. We only take people within these lines. That central curiosity leads me to start researching this issue and to surprize after surprize. It started just like a passion project, and the surprises kept coming. At a certain point, I was like, this is an untold story. I think there is a lot of stuff here that nobody [is] aware of. Even though I’d been working in education reform for a long time, I didn’t know about this stuff. And so I wanted to tell that story. So this book is that story.

Mark Gordon: The book will be released on May 17th, and that’s the 66th anniversary of the Brown v Board ruling.

Tim DeRoche: Brown v Board of ed was a famous case that ruled segregation unconstitutional, overturning Plessy v. Ferguson. That was in the fifties. And it was this case of this little African American girl. There was a school within walking distance from her house, but she wasn’t allowed to go there because she was African American. And so they filed suit, and the court said no, you couldn’t exclude people based on race. So we are making an analogous argument that schools should not be allowed to use geography, especially within a district. The legislature has drawn these districts lines to say these are the folks who share schools. I could make an argument, and I do in the book that maybe you should get rid of district lines as well, but I think the stronger argument is just to say hey, the state has drawn a line around these folks. These folks share schools, so everybody lives within the boundaries of that district deserves an opportunity to get into the best schools within that district.

Mark Gordon: On the surface, they’re public schools, but they don’t seem like that because they’re not open to the general public.

Tim DeRoche: Yeah, it’s true, and it’s even worse than I thought. Those schools operate as semi-private entities. [I live close to Mount Washington Elementary School]. I’m a constituent of the district. I’m a resident of the district, and I live in the neighborhood. It’s our closest school, but we fall just outside of that line. If I go up to the Principle of that school, even though it’s the nearest school to my house, me and my daughter, my son, and my wife, we are not the constituents for that Principle. That Principle does not think that she is beholden to us at all. For my family, we’re not wealthy by any means, but we can afford some private schools. We got the savvy to negotiate some of these choice systems at L.A. Unified. But for single parents, for lower-income folks, it’s much, much harder. It’s a much bigger deal to be excluded from these schools. And the other thing I’ll say, we found three instances in this country where there’s an elite public school right next to a failing public school. And what happens is people crowd into the zone of the elite school, so it gets very, very crowded. So young families start buying houses, paying significant premiums to purchase those houses to get into these schools, so they don’t have to pay for private school. Then what happens is the school cannot take everybody. They can’t fit comfortably in the school anymore. And what you’ve got is the poorer performing school, that is within walking distance in many cases, which has hundreds of empty seats because it’s not a great school and not that many people want to go there. So you’d think, in theory, if this is one system if this were truly a public system and you were simply re-drawing the lines every year, every couple years, to respond to population changes, what you’d expect is that the lines would change and that some of the kids at the overenrolled elite school. These elite public schools get overenrolled because young families crowd into the zone to get access to that school, so they don’t have to pay private school tuition. Then what happens is the school can’t serve everyone in the zone. The school doesn’t have space. And so what you’d expect to happen, if this were truly a system in which all the schools were in the same system, you’d expect them to re-draw those lines in response to population changes and re-designate where people go to schools to even things out. But what you find, we found three examples of schools where there were hundreds of empty seats within walking distance of a given neighborhood. But the people, the politically powerful people who had bought these homes, said No, you are not going to re-assign us to another school. We paid $200,000 extra to go to this school. So what we’re going to do, is force the school district to invest $12,000,000 or more, in some cases up to $19,000,000, to renovate the elite school, to make room in that elite school. And then does that elite school accept people who live on the other side of the line, within walking distance of the school? No, they don’t. They still only serve the people that originally bought [their house] within those lines, and the lines don’t change. The lines become very calcified over time because these politically powerful parents will never let those lines change, in most cases. And it gets very, very contentious to change the lines. And so the three examples are Marylynne Elementary in Atlanta, Lakewood Elementary in Dallas, and Lincoln Elementary, a very elite school that serves the oldtown neighborhood of Chicago as well as Lincoln Park.

Mark Gordon: You mentioned in your book about the students who graduated from the low performing schools moved on to high school, and they are illiterate.

Tim DeRoche: It’s a big problem. I knew there were discrepancies, and I knew there were gaps. Until I started looking at these pairs of schools, I had no idea how stark the contrasts are of shools that are within the same neighborhood that serve the same community. So Lincoln and Manierre in Chicago is possibly the most egregious example in the book, and there are many egregious examples in the book. But Lincoln and Manierre is perhaps the most egregious example. At Lincoln Elementary, over 80% of the kids are proficient in reading. At Manierre Elementary, in the last year, they did testing in 2019, zero percent of the eighth-graders tested proficient.

Lincoln and Manierre share an attendance zone boundary of North avenue. So if you live north of North Avenue, you’re assigned to go to Lincoln. If you live south of Manierre avenue, you are assigned to go to Manierre. Now, there are lots of middle-class parents of all races, who live south of North Avenue and work desperately hard to find some other option, whether it’s a private school or a charter school or a magnet school, to get their kids out of Manierre. However, there are still hundreds of kids who are in this school where your chances of reading at grade level by eighth grade are minuscule. In 2019, they were zero percent, nobody. And you can imagine that isn’t just affecting their reading proficiency in the eighth grade. If they aren’t proficient in reading in eighth grade, they are not prepared for high school. If they aren’t prepared for high school if they are not going to be successful in high school, how can they be prepared for college? I don’t want to claim that if you re-assign those kids to Lincoln Elementary that suddenly they would magically start performing at the same level as most of the kids in Lincoln, There is some selection going on. The people who are assigned to Manierre currently and the people who end up at Manierre, many of them are on welfare. They live in public housing. There are many problems. But it is not helping anyone for all of those troubled families to be clustered in one school. The example I love is that if you look at health clinics in the OldTown neighborhood of Chicago, you can look at two clinics, one on the Northside of North avenue and one that’s on the south side. So one is sort of comparable to Lincoln, and one is sort of comparable to Manierre. They’re about the same distance apart. Those health clinics, if you look at their ratings on Google, they are very similar. Certainly, there’s probably a little difference in the make-up of the populations that go to those two health clinics. But the fact is that because the health clinics can’t exclude people, solely based on where they live, there’s a mixing of the populations, and the level of service is higher for everyone. And so, I don’t think we are serving our low-income disadvantaged kids very well by drawing these lines. And frankly, I don’t think we are serving those Lincoln Elementary families very well. I talked to one parent who said, ‘Well, we found a townhome that we loved, a house that we love, south of North Avenue, and we thought about it, but then we found a different home that we liked less but cost $200,000 more, but we thought well, we can’t afford private school and so we might as well pay the $200,000 extra. So they overpaid for their house to get access to that school, creating these social divisions. It’s warping our society in ways that I don’t think we’ve been willing to admit to ourselves. And I’m hoping my book can force people to confront the ugliness of it.

Mark Gordon: Last year, there was the big scam with college, where actors and attorneys, and billionaires were paying to get their children into these elite colleges. I have working in education. In some ways, this kind of screams of that.

Tim DeRoche: Gloria has pointed out these people who did these enrollment frauds have gotten off with slaps on the wrists, but there are many examples in this country of low income, racial minorities, African American or Hispanic families lying about there address to get access to a good public school and the local authorities throwing the book at them. And putting them in jail for trying to access a “public school.”

People up and down the economic spectrum lie about their address in America to get into schools. I talked to a woman who raised her family in Malibu, an upper-income person, incredibly wealthy, who wanted to get her daughter, who was one of my friends, wanted to get her daughter into Santa Monica high school. So she paid a friend for her utility bill, her gas bill, and put her name on the gas bill, took the gas bill, and got here kid enrolled into Santa Monica high school. I know people, the dead center of the middle class who have done it. I know wealthier people who have done it. I know lower-income people who have done it. It is a very, very common thing in America. The only people who get put in jail are the lower-income people who are usually not the right color. It’s not a good look for our country. It’s not a good look for our public school system. the original goal was for it to be the great equalizer, that we have this free market system in which the government leaves us to our own devices. Kind of lets things sort out, and I’m a big fan of that in theory. For that to work, we do need public education, in which low-income kids can get access to the tools, knowledge, and skills they need to compete in the economic marketplace. When we have such stark divisions in terms of who gets the best access to the best schools, it undermines the social compact necessary for democracy and for our economy to work in a way that I think is consistent with that idea.

Mark Gordon: If you have children who can’t read and fall through the economic impact in the future when these children grow up, they are going to become a burden on the system. They’re not going to be able to contribute without solid skill sets.

Tim DeRoche: Yeah, and Gloria talks about the school to prison pipeline, where we put the kids in these schools that have been failing for decades, and folks who disagree with me will say, well, we need to make all schools better. Why are you talking about getting them into these elite schools, we need to make their schools better, and I would agree with that, but we have tried everything to make those schools better. It’s been decades, and some schools are failing that were failing decades ago that are failing now. They have more money now. There are different theories about how to change things like more school choice, more money, technology, different academic philosophies, curricula. The issue is that education has gone through so many phases over the past few decades, and those schools continue to fail. I would argue if you pack kids into schools where they have no other options and if they are only with other people who are struggling, that’s just not good for them, and it does create this school to prison pipeline. People consider the kids a jobs program. We got to keep all the kids in public schools because we don’t want to let go of teachers. I understand that, but then they go into the prison system, and the prison guards say, well, we got to keep the prisons full so that we have prison guard jobs. We don’t keep people in institutions to give other people jobs. That’s not how a free society should work.

Mark Gordon: You mentioned it earlier, but I want to go over this notion of redlining because it dates back years, and it kind of applies to the educational system, but it’s not called redlining, it’s called attendance lines.

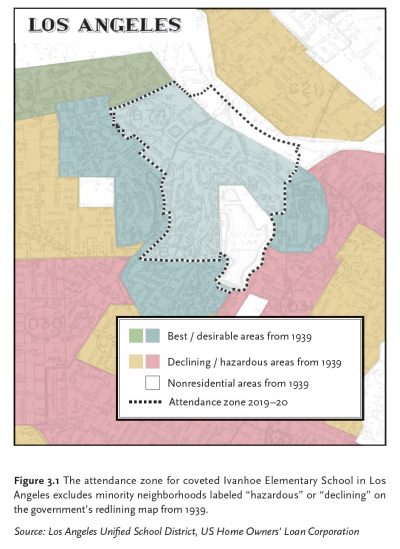

Tim DeRoche: Redlining was a practice in the 1930s. There were big housing programs created during the new deal, and an agency of the federal government needed to determine who was eligible for this assistance and who wasn’t. And they drew these infamous maps, in which certain areas of cities, if you look at the L.A. map, huge swathes of the city, like two-thirds of the city are red and yellow, which are hazardous and declining. And those people living in those areas, of any race, were not eligible for mortgages or housing assistance and those areas tended to be the areas with higher concentrations of minorities and immigrants. Again, it’s important to note; the discrimination was not based on race. So if you were a white person, a caucasian person living in one of these areas, you also were denied housing assistance. On a global level, the bureaucrats who drew those maps saw a neighborhood that had a high concentration of minorities and immigrants. They saw that as an undesirable area and so let’s not give them housing assistance.

When I was writing the book, one of the big surprises was we were creating these maps of the attendance zones, showing how these lines determine your fate, me, and my designer, Daniel Gonzales, who is just a brilliant graphic designer and artist. At one point, I wondered what would happen if we lined up these attendance zones with the redlining maps. What story is that going to tell? In some cases, Ivanhoe Elementary, here in Los Angeles and PS8 Robert Fulton in Brooklyn, you can see that the attendance zone mirrors the shape of the desirable area on the redlining map and the lines still exclude areas that higher concentrations of minorities and immigrants. Even in cities where it doesn’t overlap exactly, the point is, the analogy still holds. We’re still using lines drawn on a map to determine who gets access to the precious government services, and we’re still often excluding middle class and lower-income families of all races. I think it’s an ugly echo of our nation’s past.

Plessy v. Ferguson was the case that said separate but equal was ok. So you could have separate schools. You could have segregated schools. You could have white kids assigned to one school and black kids assigned to another school and long as they were “equal.” Of course, they never were, and obviously, that was an ugly decision. Brown v Board overturned Plessy.

So what’s happened is the courts, in terms of the schools have, Brown very clearly outlawed covert racial segregation. And the route that the courts went is that they said you could not overtly sort kids into schools by race. The problem with that is that they also said that if there’s no overt segregation, then it’s ok if the races sort themselves into different schools. And so, basically, what’s happened over time is that there are more successful segregation lawsuits because no district in its right mind would officially site race as the reason they’re sending kids to different schools. Even if that is their intent, if they can just keep those words out of their official testimony, they can keep it out of the official documents. It doesn’t matter how much actual racial divisions are in the schools, the court has said, ok, we’re powerless to do anything about these divisions because there’s no overt segregation. I think it leads to the courts being wholly disengaged from access issues, which I don’t think is healthy because in a system like we have, where these governmental entities run schools. Politically elected representatives govern them, there will always be pressures from politically powerful interest groups and constituents to try and reserve the best schools for those families. And so to have the courts completely disengaged from those issues is I think very problematic.

Mark Gordon: You write in your book about how the laws promote this notion of segregating our schools.

Tim DeRoche: That was another big surprise. So my curiosity was, in California, how does a school keep out district students within walking distance of that school. And what I was surprised to find is that in California, it’s the open enrollment law that keeps those kids out. In California’s voluminous education code, I can’t find any evidence of the legislature saying districts should draw attendance zones. There’s now overt statement of that except in this law.

So that was another big surprise that I had. I was curious about how these schools keep out different children who live within walking distance of the school. And so when I dug into it, I couldn’t find any evidence in the voluminous education code of California where the legislature says, ok school districts, you have to draw attendance zones boundaries and do it this way. The only thing I found was a clause in the 1992 open enrollment law. This is a law that meant to open up public schools to anyone in the district. That was the official stated goal of that law. The problem is it says that any kid in a district has a right to attend any school within that district, but it includes the clause that they cannot displace a student zoned to go to that school. That sounds on the surface like a perfectly reasonable accommodation. Still, with that clause, the legislature requires districts to set up these geographic enrollment preferences, and what it does is it guarantees that the elite schools will remain exclusive to people who remain in that zone. It guarantees then that wealthier parents will start to buy homes in that zone, driving up the property prices. It guarantees that low income and middle-class parents will not be able to afford homes in that zone and will believe to go elsewhere. So all of these stark divisions between schools that are right next to each other, they sprout from that one exception. Now, in different states, the laws are different. In some states, there is actually a law that says you must divide your district into zones and assign kids based on geography, and the legislature is very explicit, but in California, it is ironically the open enrollment law that keeps these schools closed to most district kids.

Mark Gordon: You talked earlier about some of the things people have done to get their child into one of these elite public schools? Also, what do the schools do because I read in your book where they will hire someone to photograph, do video surveillance, and a student, all these different techniques to prevent these kids from going to school.

Tim DeRoche: This is kind of an untold story. Education is so important. Parents are going to do whatever they can to get their kids into these schools. I talked to one woman, she was the daughter of Chinese immigrants, and they go on the wrong side of Mao, and they moved to the bay area in the 1980s. She was in Oakland public schools, she came home from Kindergarten one day and said, I’m bored, and her parents said that is unacceptable, but they were not wealthy, working-class immigrants. So, they pulled their resources, all the aunts and uncles, to buy one home in a wealthier district, and they sent fifteen cousins through those schools with this one address. As they moved up the social-economic ladder, they could afford a couple of other houses in this wealthier district, this higher-performing district. So they were trading addresses within the district to get access to the right zones so that each kid could go to the school that was the best fit for them. It’s ingenious, and I think some people would say that’s wrong. What I would say is, I don’t think it’s wrong. This is the system that has been jury-rigged against the middle class and lower-income folks. So I think you’ve got to make it work. And secondly, let’s get rid of it. We shouldn’t have those lines that prevent access to public schools. Even if you think it’s wrong, let’s try to get rid of these bad policies that encourage this behavior. It is so common. I talked to a friend and said, I am writing a book about these policies, and he said, so what. And I said people lie about their address. And he said, So what, everyone in New York is lying about their address. If everyone in New York is lying about their address, why in the world do we have these dumb policies? If people are going to get access to whatever school they want through whatever means, why are we distorting real estate prices, why are we boxing out people who aren’t willing to lie about their address. It just doesn’t make a lot of sense. What it does is create this system where some schools and some districts crackdown and hire private investigators to surveil kids. We have a quote in the book from a private investigator who takes on these kinds of gigs, and he says, you have to use a telephoto lens, and you should really have a woman investigator because when you have someone taking photos of kids early in the morning, it raises fewer eyebrows if it’s a woman. And you may think that they are breaking the law, they’re cheating to get their kids in. What I would say is, the people who are being spied on are everybody. Even if one kid is lying about their address. And I don’t think it’s right that we have a system where effective enforcement requires the spying on children. It just doesn’t feel right. And I don’t this story has been told yet. I don’t think it’s reached public consciousness that this goes on at many elite schools.

Mark Gordon: It seems like institutionalized racism.

Tim DeRoche: In many ways, these systems are emergent. So they are not the result of anyone who holds racist views, trying to exclude people of one race or another that isn’t what’s going on. There is a tendency among some folks who want their kids to go to school with people who look like them. I think that’s up and down the economic spectrum. That’s probably people of all races to some degree, but the problem is when you put these schools in the hands of politicians. The politicians are responding to powerful political interests, the people who have political power are going to use that tendency, good or bad, wanting their kids to go to a school with people who look like them, it’s going to look ugly in what that looks like on the ground. Whether there was racist intent, to begin with, or not. The results are gonna look ugly.

Mark Gordon: What surprised you most when you started to get into this material based on what you knew from your twenty years in education to now you are researching and uncovering certain things that you didn’t know about. What surprised you or shocked you?

Tim DeRoche: Number one was the stark contrast of some of these schools that serve the same neighborhood and how living on one side of the other of a street can matter a whole lot on in your educational destiny and therefore what your life destiny might be. The second big surprise that I found was that I stumbled upon this old civil rights law, the equal educational opportunities act that was passed in 1974. Everyone has forgotten about this law, but that law has a clause in it that I think is quite powerful and may impact some of these issues going forward. That law says that minority children cannot be assigned to a school that is not the closest to their residence of it will worsen segregation. And so, if you look at these attendance zones, they tend to misshapen things. They’re kind of Ameba looking things. If you look closely, in almost all the cases, you will see pockets where people now live very close to an elite public school are zoned to go to a failing school down the road. The elite public schools have much higher concentrations of white students. The district sends one of those kids who live close to the elite school when it sends some minority to some other failing school, which is almost always worsening segregation by making that assignment. One of the things I am highlighting in the book is a lot of minority parents have the right to sue in Federal court for access to these elite public schools, and I don’t think they know it. I’m sure they don’t. No one I’ve talked to in education reform movement or community knew about this law, and it’s very straight forward, and the law does say that neighborhood schools are ok. Still, I think congress knew well enough that if they just said that neighborhood schools were ok, then the districts would play games with defining neighborhoods to please more powerful parents. Son congress very specifically defines the neighborhood school as the school closest to your residence. And so, you’ve got an opening for civil rights legislation, civil rights lawsuits to get minority kids, in some pockets into these schools. I think the benefit of those laws, it won’t benefit everybody in terms of access, but a series of lawsuits based on that law could have a significant impact on raising this issue to public consciousness, and affecting the public conversation around whether these lines are just.

Mark Gordon: How does maintaining the status quo benefit the districts?

Tim DeRoche: The districts want enrollment. They don’t want to lose those students in those wealthier areas. And so you could imagine. And I have a lot of sympathy for these folks and I know my book is going to be perceived as attacking those folks but I have a lot of empathy. Anyone who is working within the current system to get their kids access to a good public education, I have a lot of sympathy for. But I think the districts are worried that if they were to open up those schools, those people would start to argue that I want other choices for my kids. Some of those folks are strong opponents of charter schools. And you have this interesting thing where a lot of lower-income, minority communities are in favor of charter schools. But you have more progressive, largely white communities, more affluent communities that say hey, we don’t want charter schools. Just send your kid to the neighborhood school. And I think that the districts are afraid that the folks who are so adamantly opposed to charter schools might start saying, hey we want some options for our kids too. And maybe we are not going to oppose charter schools because we no longer have preferential access to these elite schools based on neighborhood. That’s my suspicion, Mark, but it’s hard to tell, and there are probably multiple dynamics going on around that. The parent community around a school matters so much and how engaged the parent is. I will say that there are good examples of that and bad examples of that in charter schools and traditional neighborhood district schools, whether they be the elite schools with these strick zones or some other types of schools. There are wide differences, and some of that is hard to predict based on income. It’s hard to predict based on what type of school it is. I agree with you, that is very important for the community and the school.

Mark Gordon: Now that we are in this Covid19 world and a lot of schools have closed, and it’s remote learning, there’s going to be a real tell with this because some students, won’t have the same, they are not going to give the same chance to succeed technologically.

Tim DeRoche: Well, that’s true, and it’s even more so because lower-income kids and kids from troubled homes get less support at home. By definition, the parents don’t have as much capacity to offer help, and so I think it will exacerbate inequality in the short term, and I think it’s going to be hard to see that because it’s happening in homes and we just don’t know. And I do think that some districts and some charter schools groups are handling it well and others are not, and it’s going to be very hard to have transparency into that, but there’s no doubt that this crisis will dramatically hurt some kids.

Mark Gordon: Why are schools failing? Is it because of this gerrymandering and redlining of the school districts?

Tim DeRoche: I think that’s a complicated and big question and I don’t have a full answer to that question, and I do not want to claim that changing these laws and opening up the elite public schools like that does not solve all the problems of our schools bt a long shot. It doesn’t solve all of them, create some of the dynamics that would lead to school improvement over time, and would lead everyone to feel like they were fully invested in the system over time and fully invested in improving the system over time. I am advocating for something that I think would help over time. There are deep problems in our society. Some of which are socioeconomic. We have an underclass in this country. We probably have multiple underclasses. I think we have innercity underclasses where you have very troubled communities, wracked by violence. I believe you also have underclasses in the rural parts of America.

You might have very different racial make-ups, but you might have similar symptoms that cut across those superficially different groups. You might see some common issues. If there were an easy answer to those issues, that would have emerged a long time ago. I don’t think we know how to get rid of those problems, and I wish we did. In terms of the schools, I do think other things contribute. One of the things that contributes is the passivity with which many Americans regard school selection. I believe every family should be working their best to try and figure out which school is best for my kid. The district bureaucrats decide where your kid goes [to school] they don’t know that your daughter loves to dance and that she has dyslexia or that your son has trouble regulating his emotions but his good at math. They don’t know that and each kid is different, each family is different. If you look at the statistics published by the National Center for Education Statistics, over half of Americans just send their kid to the school where they live. Some parents pick where they live based on the school. Some kids use public school choice. Some families choose private schools or homeschooling, but over half of Americans don’t pick their residence based on the school, but they still send their kid passively to whatever school they’ve been assigned to. Education is too important. We need to move away from that. We need to start thinking about, ok, kids are different, let’s find the right fit for each kid. So that’s part of it. I do believe there are also problems in the school systems. It is hard to fire poor, performing teachers. I have my kid in an LAUSD traditional public school, and she has an astoundingly good teacher. Off the charts. And so there is no sense to which I think you should blame all teachers for the problems of Amerian education, but there is the problem that it is hard to fire teachers in these big public school systems. And when you have set-up a system where it’s hard to fire employees then the people out in the world who are perhaps lazy or incompetent or complacent or maybe they are just troubled, they are going to start looking for jobs in that system because they know that once they’re in, they can’t be fired. And you get the phenomenon of the rubber rooms in New York where people, they don’t feel comfortable putting these people into classrooms. Still, they can’t fire them because of the regulations. So you are paying all these teachers to sit in a room and not teach, or you get the problem of must place teachers, which has been a problem in L.A. Unified [School District] for decades where teachers who aren’t performing or who aren’t a good fit at their school, are kicked around the system. The district pushes them into schools because no one would hire that person because of their track record, but the district can’t fire them, so they get must place into schools where the Principle doesn’t want them and has an opening and wants to hire someone whose more competent, that’s not ideal. I think when there are budget cuts they don’t cut based on who is doing well, by law and by the teacher’s union contract, they have to fire the youngest, least tenured, people first. And you lose a lot of good teachers that way. You’re losing people who might want to make a career. They get fired, and they go and look for something else.

Sign up with your email and always get notifed of Avada Lifestyles latest news!