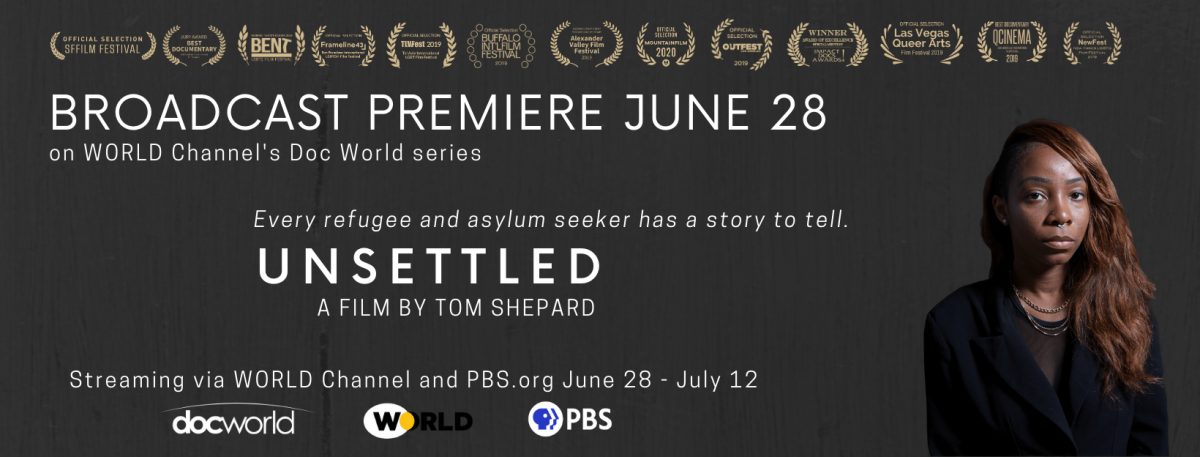

Tom Shepard talks about his latest documentary UNSETTLED: Seeking Refuge in America. The film looks at the plight of LGBTQ refugees and asylum-seekers who are forced to flee their homeland because of violence and persecution, often at the hands of homophobic family members.

Tom Shepard: In 2014, I started researching this film, and at that time, in the US, LGBTQ civil rights were accelerating quite quickly, and marriage equality was sort of steamrolled to the supreme court would become the law of the land. I was doing some refugee volunteer work at Jewish Family and Community Services, and they had just gotten a grant under Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to resettle queer refugees. I think it was one of the first in the country to do that. And I just thought, wow, this a ripe moment because state-sponsored homophobia and persecution of queer people in many other parts of the world seem to have gone up. It almost felt kind of inversely related to what was happening here in the west. And also, honestly, I’m a gay man. I live in San Francisco. Most of my friends are fairly progressive and educated, but, I don’t think one of them could have told you how a refugee is resettled, or even the difference between a refugee and an asylum seeker. So, I think I was interested in would there be an opportunity to make a film that would allow this conversation to be amplified cause I think most Americans don’t know it. It made me start thinking about all the ways in which I now have rights as a gay person in the US and appreciated how that’s not the case in other parts of the world.

In a number of countries, and we focused more on regions in Africa and the Middle East, you have, in many cases, not just, sort of, intense kind of anti-queer, anti-gay bias, but you often have state-sponsored homophobia. So, you can’t go to the authorities or police to protect you. The biggest difference, Mark, is refugee resettlement in this country, and we have a good record historically in the United States for resettling persecuted people, but it’s always been based on families. So a family will flee a war-torn zone, say in Iraq, and come to San Francisco. And immediately they’re connected in with other Iraqi, or Iraqi Americans, a mosque community center, members of their diaspora and it’s by no means easy, but there are ways to let people get their sea legs when they get here. If you’re a gay Iraqi, the last [thing] you want to see you when you come to San Francisco are another Iraqis because you’re not fleeing with family, you’re often fleeing from family. And that was the most heartbreaking thing in all of the stories that we covered. There was this intense violence that are subjects faced at the hands of their parents often or other family members. And particularly in some countries now in Africa, you have a thing called lesbian corrective rape, which is this almost culturally reinforced, like we’ve got to change these people and bring them back on the straight path to do honor by our own family. So, honor killings. It’s pretty intense what these young people have faced. When we started the project, most of the refugee resettlement folks hadn’t tuned into these specific needs and experiences of queer refugees. And often, those folks, when they get here, are much more likely to be isolated and repeated trauma, the PTSD, and then also kind of displaced again once they get here. So, I guess I was a little bit shocked at how different the experience is for a queer person.

Mark Gordon: What were some of the challenges you faced making Unsettled?

Tom Shepard: We had a really hard time funding this film at first, and then Trump won the 2016 elections, and suddenly we raised more than 60% of our budget in the next six months. I will say we are super grateful to the Independent Television Service, ITVS, for being an early development funder and then coming back and providing completion funding. The biggest challenge was finding people who would be willing to go on camera because of the persecution. Because of the trauma, they were worried about their well-being, but they were also worried about putting their family members back in their home countries in harm’s way. If their stories become too public, they’re concerned about what violence might happen in their countries of origin. I feel very lucky to have partnered closely with Jewish Family and Community Services. They got to know me very carefully and gradually and could kind of see what my approach was to the film and help me connect with some of the refugee clients that they had. And then I also felt incredibly lucky to meet a woman named Melanie Nathan, who is a powerful advocate for LGBTQ refugees and asylum-seekers in Africa. And she was following Cheyenne and Mari’s story on the ground in Angola, and I reached out to her, and she said you wouldn’t believe the story, what these women have been through. They’ve been in a relationship, and they somehow got a student visa and will be arriving in San Francisco next week. And I just dropped everything to meet them. But that relationship took time. It was weeks and months for them to understand what the nature of my film was and what my sensibility was and for them to start to trust, to open up some of their stories.

Junior, Mari, Cheyenne and Subhi

I think that’s useful about our film because subjects who agreed to participate all have very different experiences. They’re obviously from different places, but their resettlement experiences, their first years in the US, were quite different. Subhi Nahas, a gay refugee from Syria, fled as the war had started the year before, and he had an intense conflict with his father, and so he was able to flee to Lebanon and then ultimately to Turkey. And I met him via Skype before he came to the US, and so I was able to hear and understand his backstory. He hadn’t been in the United States for three months, and then he was invited by then-ambassador Samantha Power to the United Nations to speak before The Security Council. First time for a gay person to testify in front of that august body. That’s not a typical refugee resettlement story. He immediately became a sort of poster boy for refugee rights. Many, many people were writing to him, Press of course, but also people who are stuck in their countries, sort of saying how did you do that and how can I do. And I think that must’ve been incredibly overwhelming for him for a year or two. Part of him just wants to find a normal life and have a normal existence. So, that story juxtaposed to Junior Mayema, whom I also met through Jewish Family and Community Services, was an activist and a law student in Kinshasa in Congo. I think he was targeted because he was so out there, and his mother is sort of a fundamentalist preacher and had said some pretty horrific things about gay people and would have to kill her kids if they were gay. And so Junior fled quickly and went to South Africa, thinking that Cape Town would be a refuge for him but ran into the same kinds of anti-gay persecution, police brutality. He filed a claim against the police in Cape Town, and at that time, the United Nations expedited his refugee status and got him papers to resettle in San Francisco.

Junior Mayema

His experience in the first year was super challenging. He must’ve moved ten times in the first 10 to 12 months when he was there, which both sort of underscored the fact that our city was just beginning to come to terms with how we house folks. Middle-class people can’t even afford to live in San Francisco now. Try living there on a refugee benefit of $325 a month. So Junior was couch surfing and was experiencing almost a repetition of that kind of displacement, and I think that affected him to his core. So he ended up in a homeless shelter, which was something that we filmed and had been struggling with but was finally able to get a public housing accommodation in San Francisco.

Those guys struggled as refugees and gay men, but it’s nothing compared to asylum-seekers, particularly women. And when I learned about Cheyenne and Mari’s case, one, that these two women had the wherewithal to form their relationship, and have this loving relationship in Luanda, Angola, and they were pretty successful. They’re dancers and singers, and I think Mari had even been a finalist on a sort of American Idol type show in Luanda. They were successful popsicle entrepreneurs. They had a little business, so they were doing well, but their neighbors and their family members, started to harass them pretty intensely when they found out they were a couple. And so they fled on a student visa and came to the US. They had to adjudicate their asylum case and get a pro bono attorney, and it took about almost three years to work their case through the system. It’s intense. Women from that culture, and some of the other cultures we followed, are expected to get permission even to leave their cities, let alone countries from men, from their fathers, from uncles. So for these women to have the fortitude to make it to the US, and then be able to support themselves, asylum-seekers don’t get any refugee benefits, they can’t get their work permit for months after they file their claim they have to have a lawyer. It was nothing short of miraculous that these two women navigated the system here in the US.

It was quite a learning process for me to work with these folks because we followed them for almost four years, and of course, we’re still working with them, and I knew very little about refugees. I knew sort of the basics of US immigration policy, but couldn’t have told you much about the refugee experience, let alone LGBTQ refugee experience. And they’re all trauma survivors, so the trust stuff was challenging. It took a while to develop some of the rapport. I so admire them for being willing to expose their stories so soon after they had gotten here.

Mark Gordon: How do you build rapport?

Tom Shepard: Well, documentary is so much predicated on access and relationship building. The craft part of it, of course, you have to hone that, and the storytelling is critical, but in my time, I think, just as I’ve matured, maybe I’ve become more sensitive as an older person, my ability to connect with people, and hopefully try and create a space that enables folks to be heard and seen, has developed over time. And I teach a lot, and I have to say that’s become a real key for me. I teach every summer here in Colorado Springs with young filmmakers from underrepresented backgrounds, and they keep me very fresh. We’re talking about this stuff all the time about how do you connect, how do you stand in the shoes of other people and other experiences. And this idea of very thoughtfully investigating people. And I see my students do it, and that inspires me to want to do it as well.

I think it’s a lot of active listening, and this idea of making it clear to them that you’re seeing them. You’re hearing what they’re saying and that you’re incredibly empathetic, that you can hold this, that whatever pain it is that they are holding or their tangles that need to be smoothed out, you can hold it. I find having a microphone and a camera there often helps the process, which is sort of counterintuitive because you think, wow, it’s so formal, and that would create nerves. But I think for a number of the subjects, they see this whole apparatus as interested in hearing them, listening, holding whatever pain, and struggling. And I think people like to be heard and like to be seen, and we live in a culture that’s a little bit about the loudest voice wins. Not everybody is the best listener in the world. And especially these folks, whose single strategy for surviving in their countries was to be silent, was to be invisible within their own families. So, suddenly to have these empathetic people, producer, director, even our camera people are the most sensitive, empathetic people you’ll meet, all tuned in two I want to hear what you have to say. That’s pretty powerful.

Mark Gordon: What was your intention in making the film?

Cheyenne & Mari

Tom Shepard: I love something that Mari says in the film, which is that most Americans when they think of refugees, they think of poor, uneducated criminals. People who want to steal jobs from Americans. All of the people we followed were highly educated, but we’re in a system in which they had to remain silent about who they are and who they love, or they were going to face huge harassment. When Trump followed through and much of the anti-immigrant rhetoric that energized his campaign. It’s been pretty striking. The number of refugees now allowed into the US, since Trump has been in office has been cut by 80%. So while the US used to be the safe harbor and resettle more refugees than any other country in the world, we are now at a historic low. Despite the fact that all these people we filmed, helping refugees in San Francisco create this new kind of new infrastructure, the number of refugees coming into the country is down to a trickle. Our approach as filmmakers is to try and humanize for a broad American audience who refugees are. What are their lived experiences? Not just their persecution, but what are their hopes and dreams, and talents. And so that’s the part that I think the film plays, but I think what the public can do is engage with their representatives and with Congress, especially right now. The country’s attention is focused on black lives matter. Three of the four-film subjects are black, but they’re also refugees, and they’re also queer. So I think educating folks is the best place to start.

Mark Gordon: What impressed you most about the refugees and asylum seekers you met while making this film?

Tom Shepard: The thing that impressed me most about all the folks we followed is the resilience that they were able to tap. I think they were in life-threatening situations back home and then faced transitions in their acculturalization and resettling that nobody anticipated. And that they kept on surviving these difficult experiences made me realize that as someone born in Colorado Springs, I’m entitled to all these basic things: a place to live, connection to family, knowing how to work my way through the world. It amazes me how they survived. If you look at people in the US and Europe who are out on the front lines during the COVID crisis, many refugees who have been resettled are the ones doing that work. It doesn’t surprise me at all. I think many of them are crisis competent and not afraid to engage in these difficult times and these difficult experiences.

Mark Gordon: What did you learn about yourself from working on this project?

Tom Shepard: I grew up in one of the more conservative towns in America, Colorado Springs, at a time in the 80s and 90s when Colorado Springs had become ground zero for the religious right. You have Focus on the Family, the New Life Church, and you have a strong military establishment here with the Air Force Academy and NORAD. So, being an openly gay person, growing up in Colorado Springs, was very difficult. I kind of understood internally to be a gay man, and to be a documentary filmmaker, I probably wasn’t going to be able to stay in the Springs. My experience, in no way compares to Subhi or Cheyenne and Mari, or Junior, but I understood the need to flee. And at that time, San Francisco was the emerald city. And I could go there. At that time, I could live with roommates for $300 in an apartment in the Mission. And I could find my tribe, both as a filmmaker, there’s such a strong film community there, but also as a gay person. And I think the subjects of our film had that same mythology of what San Francisco was, a promised land for queer people. But as I said earlier, try living in San Francisco now, even on a middle-class income. You can’t do it. Teachers can’t do it. Firefighters can’t do it. People are leaving the city in droves, including artists and filmmakers. I think one of the questions that became central, which I wasn’t expecting when we started the project, is whether cities like San Francisco and New York have obvious choices for queer refugees to be resettled? Are they the same, sort of, sanctuary cities or refuge cities that they used to be? And the film looks at a place like San Francisco and the change in the character of that city. So I split my time now between San Francisco and Colorado Springs. It raised some fundamental questions about my city, both cities.

Mark Gordon: Tell me about your creative process in making a film.

Jen Gilomen & Tom Shepard

I think the process is reading and talking with friends and colleagues, and then, of course, so many things have to happen, Mark or a film to take root, and access is such a huge one. That was tricky early on, but these projects often feel like you’re pushing a Steinway up the side of the hill, and you have to stop a number of times. You have to bring on a number of Sherpas who are capable, and that’s always served me very well on every film project, is that the people around me are the people that I love and trust. Often many of them are mentors as well, so I am learning and engaging as I’m making the film. The best way to learn filmmaking and hone filmmaking is to be around people who share the benefit of their work.

One of my long-standing mentors is Jim Klein, who, for me, has been a kind of surrogate parent, teacher, mentor, colleague, and we started our collaboration with Scouts Honor back in the late 90s. He’s a giant in our independent documentary filmmaking, field, and he’s got such incredible mentoring instincts. And he often would bring the conversation back to where is the humanity in the story. And also, where is the emotion in the story. When I was a young kid, documentary wasn’t so interesting because it was very expository. It was very educational. Those instructional film strips that we used to watch in class about the reproductive system. That’s kind of where the documentary was for me. Still, Jim opened the doors to this whole body of work, the Maysles Brothers, of Barbara Koppell, of he and his filmmaking partner Julia Reichert and how people can take the cameras and tell their own stories. As filmmakers, we’re there just to facilitate and create an environment where people can step forward and tell their personal stories. So, Jim has been a huge, initial informative, and now continues to be one of the biggest film making influences in my life.

Mark Gordon: What would you like an audience to go away with after they see your film?

Tom Shepard: I think the reason we made the film is to really like humanize who refugees are and of course, in particular, LGBTQ refugees and their experiences. So I want people to feel more than anything just to connect to what’s happening on the screen. If you open hearts, then you’re bound to open more minds. If someone feels something for Cheyenne, Mari, or Junior, Subhi, they’re going to be more likely, when they see an article in the New York Times about refugees to read it. Maybe they hadn’t before. Or they might be more likely to volunteer with local refugee rights organizations in their city. So it’s all about an emotional connection that can then be a starting point for action to make the world a better place and make the world better for refugees and all of us.

The film has its national public television broadcast on Sunday, June 28, 10 PM eastern time on a series called Doc World, which is distributed by World Channel. Then it will be streaming on www.PBS.org and worldchannel.org for two weeks in July.